I couldn’t help but read Reign of the Fallen, Sarah Glenn Marsh’s epic fantasy debut, alongside Rati Mehrotra’s Markswoman, another debut epic fantasy novel published on the same day. Both books have as their protagonists young women with special skills—Mehrotra’s an assassin from an order with telepathic skills and quasi-magic, quasi-technological swords; Glenn Marsh’s a necromancer capable of raising the dead nobility of her kingdom back to their facsimile of life, and thus preserving both their changeless ruler and their connection with their families—who are faced with challenges to the stability of their worlds.

But Reign of the Fallen opens with a brilliant first line and a gorgeous sense of voice.

“Today, for the second time in my life, I killed King Wylding. Killing’s the easy part of the job, though. He never even bleeds when a sword runs through him. It’s what comes after that gets messy.”

Conversely, Markswoman opens with a classic case of worldbuilding infodumping, in the form of a bland expository passage from a fictional history, an extract from “The Orders of Peace – Our Place in Asiana,” and never quite achieves Reign of the Fallen’s compelling and seemingly effortless fluency of voice.

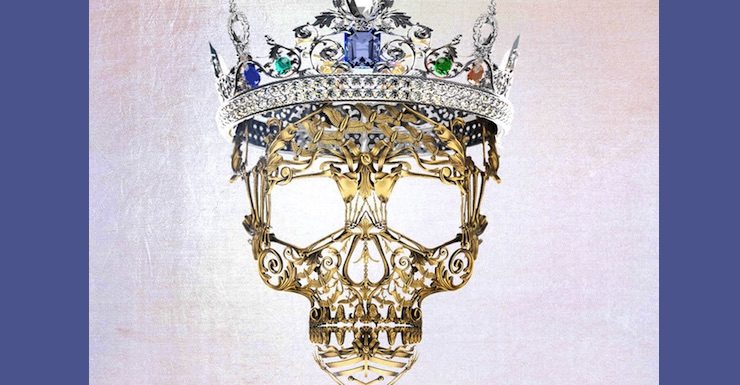

Buy the Book

Reign of the Fallen

That intangible known as voice can help a novel over a number of hurdles. And in Reign of the Fallen’s case, it does—from the near-complete isolation of Karthia, the island nation where Reign of the Fallen sets itself (and which hasn’t, it seems, seen so much as a shipwrecked foreigner on its shores in centuries, despite a thriving all-island trade by sea); to a rough patch in the middle of the book where the pacing sags while the main character retreats from grief into poor medication decisions and self-pity. Reign of the Fallen has voice in spades.

Odessa is a young master necromancer in Karthia, a country that has been ruled by King Wylding for centuries. When Karthian aristocrats die, many of them—or their families—chose to have a necromancer find their spirit in the Deadlands and bring them back to inhabit their dead flesh once again. But Karthia’s Dead cannot be seen, or touched, by the living: their flesh must be heavily shrouded or veiled, because if they’re seen by the living, they’ll transform into monsters known as Shades—beings made entirely of hunger and rage who can only be killed by fire.

Together with her partner and lover Evander, Odessa witnesses a Shade murder her mentor on the day she resurrects the king. She, Evander, and a handful of their peers are determined to avenge their mentor’s death and destroy the Shade, but the attempt goes badly. Evander dies, sending Odessa into a spiral of grief, depression, and painkiller abuse, and rendering her judgement rather questionable just at the point where it’s most important for her to be thinking clearly.

Aristocratic Dead have been going missing, including the parents of the living heirs to the throne—a young woman called Valoria, an inventor in a nation where change is all but forbidden; and Hadrien, her elder brother, who displays significant (quasi-romantic) interest in Odessa. Complicated Odessa’s feelings is the presence of Evander’s sister Meredy, just returned from her own magical training, who resembles Evander closely, and who is grieving the untimely loss of her own lover. Odessa and Meredy forge a fraught and complicated alliance/friendship/relationship during Odessa’s week-long struggle with substance abuse—just in time for the king himself to go missing.

If Reign of the Fallen’s voice were less strong, I’d be inclined to cut it a lot less slack. Odessa’s deep grief is perfectly understandable from the point of view of an 18-year-old who’s just lost both a parent figure and a lover, but the novel treats her approach to using painkillers to deal with her grief a lot more lightly than this sort of material really deserves. And I’m rather dubious about the fashion in which Odessa transfers her attraction for Evander to his (younger) sister Meredy, an attraction that appears to be mutual: the way in which these two young women relate doesn’t seem entirely healthy to me. Too, several of the secondary characters are slight and underdeveloped compared to the weight the narrative eventually wants them to carry.

But Sarah Glenn Marsh has written an impressively readable book. Odessa is a vibrant character, and her first-person narration carries the reader easily along. Apart from a couple of pacing wobbles, Reign of the Fallen builds tension effortlessly. Its action scenes are tight and interesting, and its politics, while peculiar, make sense in its context. (Odessa sees the rule of the Dead as benevolent because from her perspective, they are. Glenn Marsh doesn’t spend a lot of time on economic consequences—I’m a logistics geek, myself: where do you put all these minimally-productive-but-still-consuming-lots-of-resources dead people? What does this do to the demographics of your aristocratic class and its relations with the classes that support it?—but she does gesture towards class-based discontent.)

Reign of the Fallen is an entertaining and accomplished novel. It’s fast and it’s fun, and it’s set in a world that’s refreshingly free of obvious hangups about sex and sexuality. Hopefully Glenn Marsh will continue to deepen her characterisation and worldbuilding in forthcoming novels—for while Reign of the Fallen is a complete narrative in itself, I hear there’s a sequel coming, too. And I’ll be looking forward to reading it.

Reign of the Fallen is available January 23rd from Razorbill.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, is out now from Aqueduct Press. Find her at her blog, where she’s been known to talk about even more books thanks to her Patreon supporters. Or find her at her Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.